Every Black History Month, WWE airs vignettes centered around historical figures like Dr. Martin Luther King or Rosa Parks. There’s usually some obligatory clip of Superstars visiting a museum or historical site, where they give testimonials of what they learned. Surprisingly, they never showcase the contributions of the first black women professional wrestlers.

Granted, they usually post listicles or slideshows acknowledging the most noteworthy black wrestlers on WWE.com. However, those posts don’t include women like: Ethel Johnson, Babs Wingo, Kathleen Wimbley, and Marva Scott. Even when they did include Scott in a photo gallery last year, it felt empty, because it didn’t illustrate why she is such an important figure in pro-wrestling.

Now, there are many other issues with the way the company presents African-American history. But, the exclusion of black women seems even more jarring, because they don’t hesitate to spotlight other legendary women all year round. Mae Young, Sherri Martel, and even Fabulous Moolah are well-known among modern fans. Surely, February would be as good of a time as any to introduce such black women to fans who’ve never heard of them.

Lady Wrestler: The Amazing, Untold Story of African-American Women in the Ring premiered at Film Festival of Columbus on Jun. 17, 2017. The documentary tells the stories of Babs Wingo, Ethel Johnson, Marva Scott, and dozens of other African-American women. Incidentally, it gained national attention just last year; following a screening at Wexner Center for the Arts at The Ohio State University in March.

The director, Chris Bournea, is a journalist based in Columbus, Ohio, which was the heart of women’s wrestling during its golden age. Like the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League, women’s wrestling emerged in the United States during World War II. The newfound opportunities for women paved the way for Mildred Burke to become one of the most popular performers at the time.

Burke’s then-husband, Billy Wolfe, essentially ran women’s wrestling during this era. After joining the National Wrestling Alliance, he worked as a trainer and booker, lending his troupe of women to several promoters and territories throughout the United States. Following Jackie Robinson barrier-breaking accomplishments, Wolfe was instrumental in recruiting not just real athletes, but black women as well.

Much has been said about him and his methods, but despite any of his other flaws he wasn’t prejudiced. Wolfe just wanted top-level female talent with drawing power. Babs Wingo and Ethel Johnson were his first black recruits. The two sisters took up judo, gymnastics, and strength training, as well as their wrestling training. Their friend, Kathleen Wimbley, and younger sister, Marva Scott, joined them in the following years.

The four women often performed in the main event of shows, with Ethel usually going over. Johnson, who debuted when she was 16 years old, is largely credited as the first black woman wrestler. Babs started training before her younger sister, but the consensus is Ethel made her in-ring debut first.

Johnson, the more naturally athletic of the two, used standing dropkicks and a version of the flying headscissors, so she worked as a babyface to Wingo’s heel. Babs would use more of mat-based style, including an arm wringer or other basic holds, but they were both ahead of their time. They were definitely worlds above the hair pulling and slapping women’s wrestling regressed into later.

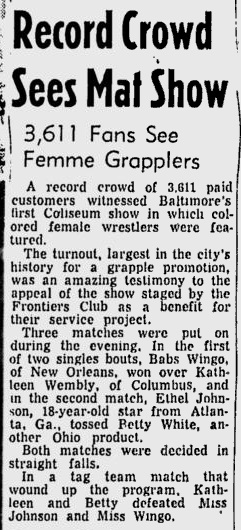

In 1952, Johnson, Wingo, and Wimbley worked three matches, including a tag match as the main event. The Baltimore show brought in a record crowed of 3,611 fans. By 1954, Johnson and Wingo received top billing at the Municipal Auditorium in Kansas City, where they drew in 9,000 customers. They both eventually challenged Burke, who helped train them, for the NWA World Women’s Championship.

In the late 1950s, Johnson went on to work with other legends like June Byers and Penny Banner. She even developed a working relationship with Stu Hart. She worked for his promotion, Big Time Wrestling, before it became Stampede Wrestling.

Johnson also worked for Jess McMahon, Vince McMahon’s grandfather, at Capitol Wrestling—the precursor to the WWE we know today. However, she didn’t get to live out her dream of wrestling at Madison Square Garden, because women’s wrestling was banned in New York, during her active years. Also, her generation came before Jess McMahon and Toots Mondt’s World Wide Wrestling Federation (WWWF) became a fixture at Garden.

Mildred Burke and Billy Wolfe eventually went their separate ways after a messy divorce. In addition, Wolfe used his influence, and the fact that women weren’t allowed at the yearly NWA conference, to get Burke frozen out of the NWA and eventually forced her to drop her title in a notorious shoot match. The dissolution of their company left black women wrestlers in a tricky situation, because Wolfe had given them a chance, when no one else would.

All the work he put into discrediting Burke tarnished her championship reign and forced her to work overseas in Japan. Subsequently, their bitter rivalry caused all the women loyal to Mildred to refuse to work with Wolfe, who basically had a monopoly on women’s wrestling, up until then. As a result, Fabulous Moolah stepped in to fill the void they left behind, acting as a trainer and booker.

This is important, because it led to the regression of the sport here in the United States. Besides the immoral and salacious aspects of Moolah’s business, she wasn’t as technically sound as Burke, so she ushered in an era of “catfighting” in women’s wrestling. It took the sport decades to overcome stigmas she created and compete with the standard that lived on in Japanese promotions.

Given these points, the damage done to black women’s legacy in wrestling can’t be understated. Burke and Wolfe’s split possibly stopped any of the women from reaching the heights they could’ve reached. Racism and sexism played a part as well, but there wasn’t a black women’s world champion in America until Jacqueline won the WWE Women’s Championship in 1998; over two decades after Sandy Parker became the first black woman to win a major women’s World Championship in Japan. Jazz became the first black NWA World Women’s Champion in 2016.

Ethel Johnson, who sadly passed away last September, deserves so much more recognition in the industry. More fans need to know about women like: Babs Wingo, Kathleen Wimbley, Marva Scott, Ramona Isbell, Sandy Parker, and Sweet Georgia Brown. WWE, the biggest wrestling promotion in the world, has the platform to raise awareness about them. Instead, they produce superfluous vignettes that rehash basic African-American history that most people already know about.

What do you think about WWE’s use of women of color in wrestling?